La cheffe opératrice Alice Brooks, ASC, à propos de Wicked: For Good

Riding on the broom of 2024's smash-hit movie musical Wicked comes its second part, Wicked: For Good, about the fractured friendship of two young witches, Elphaba (played by Cynthia Ervio) and Glinda (Ariana Grande). A year ago, cinematographer Alice Brooks ASC discussed shooting the first film and working with Panavision to develop lenses that would best capture director Jon M. Chu’s vision of the magical world of Oz. For the release of Wicked: For Good, she speaks to the distinctions between the two parts, and how the second is darker, murkier, and includes some of her favorite moments.

Panavision: Was Wicked: For Good shot at the same time as Wicked?

Alice Brooks: Most people don’t know — and it’s mind-boggling to them — that we shot these movies simultaneously. In the morning we could be shooting the end of movie one, and in the afternoon we could be shooting a scene from the end of movie two on the same soundstage. The first song number we shot was ‘Popular,’ which is in the first film, and the second number we shot was ‘Girl in the Bubble,’ which is in Wicked: For Good. We also had to shoot out Jeff Goldblum [who portrays the Wizard of Oz] in four weeks for both movies. We were bouncing all over the place, which made it tricky to keep track of everything. I knew we needed to build a visual roadmap as big as Oz itself to be able to keep five hours of movie in our heads throughout the 155-day shooting schedule.

Was it always going to be two movies?

Brooks: Once Jon Chu came on board, it became two movies. There was a desire not to cut any of the songs out. In many adaptations of stage musicals, you often you lose numbers — it’s just too hard to do all of them [in a single movie]. Our intent was to create two distinct movies that would work as a whole, and we had two distinct visual styles as well for each film.

How did you and Jon individualize each of the two films?

Brooks: Jon and I break down a script by talking about emotional intentions the way you would with an actor — to me, the camera is another character in a movie, lighting is another actor. Jon and I figure out single-word emotional intentions per scene. In the first movie, we used words like ‘yearning,’ ‘desire,’ ‘power,’ ‘friendship’ and ‘choice.’ In the second movie, we used words like ‘sacrifice,’ ‘surrender,’ ‘separation’ and ‘consequence.’

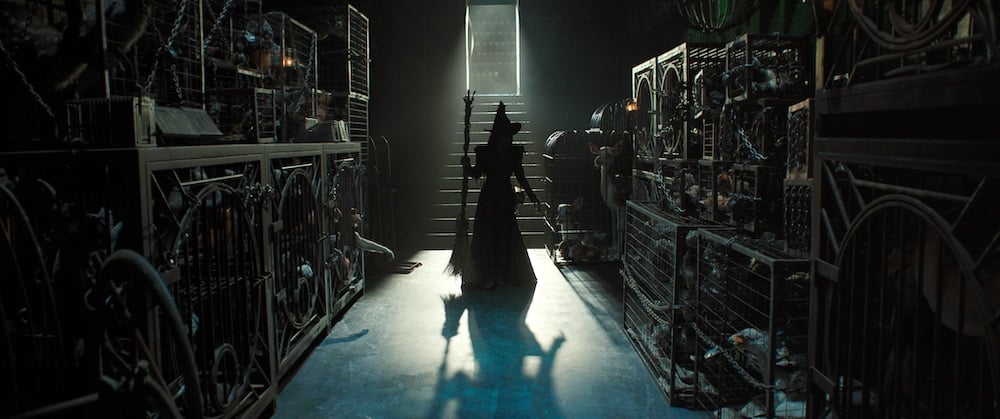

Early on in our conversations, it became clear that the first film would live in an effervescent glow of daylight, and the second film would be steeped in a maturity and a density of shadow. Tonally, they're literally night and day. The first hour of the first movie is all day exterior, and 90 percent of that movie is day. The second movie, 90 percent either takes place at night or in the underbelly of Oz, the secret, hidden places in the shadows.

How did you prepare for a simultaneous shoot of two films, each with its distinct tone?

Brooks: We started with emotional intentions. The second step was image collecting. Jon told me we were doing Wicked when we were in post production for In the Heights, and we had two years in prep, while he was splitting the script, when we were talking about story and sharing all these images with each other.

We had thousands of images in an image bank. Once we had the final scripts, I created something I call a ‘color script,’ which is a term used in animation, where you hand-paint a frame from each scene and then you can see the entirety of your film. For Wicked, I took a frame of a movie reference, a painting, a still from my camera tests, or some concept art from the art department, and I put it on my wall. The map started with movie one, scene one, and ended with the last scene of the second movie. When you step back and soften your eyes, you can see how the tonality shifts, how the color shifts. You get a sense of the entire scope of the film, but also the visual arc in each movie as well.

In the map you could see the last 40 minutes of the first movie is one long sunset, which ends when Elphaba jumps off the Emerald City tower, finds her power, and flies off into the night. That action sets the tone for the second movie, and it's where the colors start to shift, where the shadows start to come in, where our blacks become inkier.

Visually, you don't want to hit the same note repeatedly for five hours, or even for two hours. There should be a shift, like there's a character arc. So there's a visual shift within each film, and a visual shift in the continuum of both movies as a whole.

How did you manage your team to help realize this vision?

Brooks: It takes an enormous amount of people to make a movie, and an even greater amount of people to make a movie like Wicked. I had a team of over 200 people, and I needed to get all of them on board with what this vision is and be part of the storytelling with me. We made weekly at-a-glance packets, which included the script pages for the week and the color script. They also included our one-word intentions, lighting diagrams, and any information that we could feed everyone so that they knew exactly what the plan was for the week.

What is it like to work on such a large-scale production?

Brooks: Jon Chu is a person who says, 'No egos are allowed on set.' He is like a kid in a candy shop, wanting to create a fantastical world. He loves to play and create. Over and over, he kept hammering into everyone that he wanted this movie to feel handmade. He got the studio to build sets bigger than studios build anymore. We built sets like they did for Spartacus or Ben-Hur, these giant sets. We shot on 17 sound stages, and within those were 73 iterations of sets. The studio sets were 45 feet tall, and our outdoor sets were 65 feet high, so we could almost get everything in camera.

Did you use much bluescreen?

Brooks: I just created a photo diary of my experience on Wicked. I broke it down by each soundstage that we shot on, and I could not believe how little bluescreen was in my photos for being such a huge movie. We always came from a place of, ‘Let’s build it, let’s light real spaces, let’s have actors be able to interact with all the things in a space, and let Jon be able to shoot 360 degrees.’

We have so many 360-degree shots in our movies. We also do live lighting cues like the stage show does, because it brings in an element of imperfection. We're not designing lighting that goes into our dimmer board to time code. Instead, the dimmer board operator and the gaffer are live-pulling all the cues based of what the actors are doing while they're singing live, so none of our takes are exactly the same. There's a level of human beings, real people, with all their imperfections, making this movie. We shot it on a very shallow depth of field, so if something buzzes, it's because a person did it.

Can you elaborate on how you used focus to support the storytelling?

Brooks: We let our focus be shallow because we wanted to be right in there with our actors. We wanted to feel what their emotions were. We wanted to understand every single choice they made.

There's a shot of Glinda in the second film, where she makes a choice to be truly wicked, and it's a handheld shot. We used lots of handheld in the second movie, which was not something we did in the first movie. You see her walk from a medium shot into a close-up, and there's a dialogue scene happening behind her, out of focus, between the Wizard [Jeff Goldblum] and Madame Morrible [Michelle Yeoh]. We never covered their dialogue. It's in a room called the control room, which is behind the Wizard's head. We turned off all the lights, except the practical perimeter lighting, which were these 300-watt light bulbs. Glinda walks up, and she's lit with this tiny light dimmed way down, and you're so close to her. It's the closest we've been to her in either movie. You watch her think things through and make a decision, and then she whispers the decision.

Jon came up to me after the first take, and he asked, 'Alice, does she have enough light on her face? I want to make sure we can 100-percent see everything she's thinking.' I said, 'Jon, it's perfect. You can 100-percent see it.' It's become one of my favorite shots in the whole movie.

How did you decide to work with the prototype Ultra Panatar II lenses?

Brooks: I called Dan Sasaki [Senior Vice President of Optical Engineering and Lens Strategy at Panavision] the second I got the movie, and we started talking. At the time, we were going to shoot on the Alexa LF. He said, ‘I’m starting to develop a set of lenses. I’ve got one. Let’s test it and see what you think of it. Then I can adapt it to whatever you want it to be.’ We started talking about lens flare, color, and contrast, and he asked me to share references with him. We went back and forth for a while.

When we decided to shoot on the Alexa 65, Dan said he didn't have enough time to make the lenses cover that sensor, but then we pushed the shoot for six months. I called Dan and asked, 'Can you make the lenses for Alexa 65 in six months?' And he did. It was a constant conversation about focal lengths I needed, focal lengths I didn't need, the level of contrast, what filtration we were going to use, how it rendered color, everything.

What flare did you want for your lenses?

Brooks: Dan gave a whole bunch of options, and amber felt like the right choice for Wicked. Each color means something in Oz, and warm orange is the color of Elphaba’s transformation. In the second film, she’s often at a location called Kiamo Ko Castle, and we use real flame there to light her, these beautiful torches. The amber complemented the green, it complemented the pink. I knew a blue flare wasn’t what we wanted.

The lenses are 1.3-squeeze anamorphic. Do you have a personal inclination to shoot anamorphic rather than spherical?

Brooks: I feel like it’s the way my eyes actually see. I’m very nearsighted, and I don’t put my contact lenses in for the first hour or two of the day. I can’t see past 10 inches in front of me. But I like the way the world looks that way. I like sitting and looking at a view, like a deep vista, without glasses on. I like seeing all the colors that are rendered without anything being in focus except something very near to me. That, to me, is what anamorphic is. It is the way I see the world. We all put our own handprint on this movie, and for me, part of that is the lenses we chose.

What did you discover about the lenses as you used them?

Brooks: When I did lens tests, we found that on Cynthia Erivo, the 65mm lens, with a 10-inch close focus, was amazing for her. For Ariana Grande, her hero lens became the 75mm lens. In the second film, I used those two hero lenses again for both the women except for the very last scene in the movie, when Glinda finds her true power and finally realizes what goodness truly is. I shoot her on Cynthia’s 65mm lens as a nod to making part of Elphaba live on in Glinda.

Close-ups were a key visual ingredient of the first movie. Were they as important in your shot selection in the second film?

Brooks: I think they’re even more important in this movie. The second movie is so much bigger in scale than the first movie. The first movie is about kids in school who become best friends and about their choices. The second movie is about the consequences of those choices.

We're in a huge, vast Oz, but Jon and I wanted this movie to feel like it was from the inside out, not the outside in. There's restraint and simplicity to the way we made the second movie. It is quieter. We linger longer on shots. We linger on close-ups for a very long time. We get closer to the characters in this movie than we do in the first movie. There's a level of intimacy and silence with the camera, too. Some of my favorite shots in this movie don't move at all.

Towards the end of the movie, when Glinda and Elphaba have their final moment together, we did it as an in-camera split screen. Elphaba hides Glinda in a closet at Kiamo Ko castle, and we ripped out the side wall so we could see Glinda facing the door and Elphaba facing her. They both have this moment together. We could've done it where we'll shoot Elphaba's side, we'll shoot Glinda's side, and then we'll put it together in post, but every choice we made was tangible, and Jon wanted the women to be able to say goodbye to each other within the same frame. Glinda is bathed in this cool, shadowy light in the closet, and Elphaba is bathed in the warm orange glow of the torch lights outside of the closet. It's sad and beautiful and tragic. For me, those are the moments in this movie that I love.

I was at IMAX earlier today, and someone asked me what my favorite scene is. I said it's all the close-ups, seeing them projected that big on a screen. I love them.

Did you use a diopter at all?

Brooks: We used a diopter in the second shot in the sequence, where we got closer to Glinda. We needed to be closer as something else happens outside the closet that she’s trying to see. So for Glinda, we used a close-focus diopter and let the human beingness of mistakes happen in it. She goes in and out of focus throughout as she’s breathing, crying and sobbing.

Did you and Jon have any influences or references for these close-ups?

Brooks: Memoirs of a Geisha was a huge influence for us, and lots of Terrence Malick films. Tree of Life we watched, and The New World. Badlands in particular has these amazing Sissy Spacek close-ups.

The Ultra Panatar II lenses were born out of the prototypes you used on these movies, and Dan Sasaki credits you as having a major impact on their design.

Brooks: There was no name for them at the time of the shoot, so we called them the ‘Unlimiteds,’ since ‘unlimited’ is a lyric that is repeated throughout both films. Having someone like Dan and Panavision involved, I just know I can do anything my brain thinks of. Any dream I have, I can call him, and he knows how to take what is in my head and make it a reality with glass. He’s poetic in how he designs lenses. I don’t know how he does it, but I do know the results have been magical on our movie. I love every single thing about the way our movies look.

You’ve worked with Jon M. Chu going all the way back to film school. How has your creative collaboration with him changed over the epic production of these two Wicked films?

Brooks: It’s amazing to make a movie with your friend — not because it’s comfortable, but because it’s uncomfortable, because you can be more honest than you can be with anyone else in the world. Any other director I work with, I’m learning their style, what I can and can’t say. With Jon, we’ve worked together for so long, we’ve known each other more than half our lives, I just say whatever’s in my head. I’m completely honest and vulnerable with Jon, and he’s the same with me. We are constantly pushing each other. We are always demanding greatness from each other. We’re encouraging each other, we’re supporting each other. We can disagree with each other, but we’re both fighting for the same thing, and that’s to make the best movie we can make.

I think that for all great movies, the only way they're great is if you are standing on the edge of the unknown and you're able to take this giant leap. We're making a movie about friendship while we're knee-deep in dirt, on these huge, vast sets, doing something no one has done. We were making movies one and two in tandem without having a clue if anyone would ever go see the first one. We've had huge successes, but we've also had failures together, where the opportunities and the jobs we think are going to be our next big break don't work out. But we always come out on the other side. Because we know we're together.

Unit photography by Giles Keyte, courtesy of Universal Pictures. Frame pulls by Alice Brooks ASC, courtesy of Universal Pictures. Additional images courtesy of Alice Brooks.